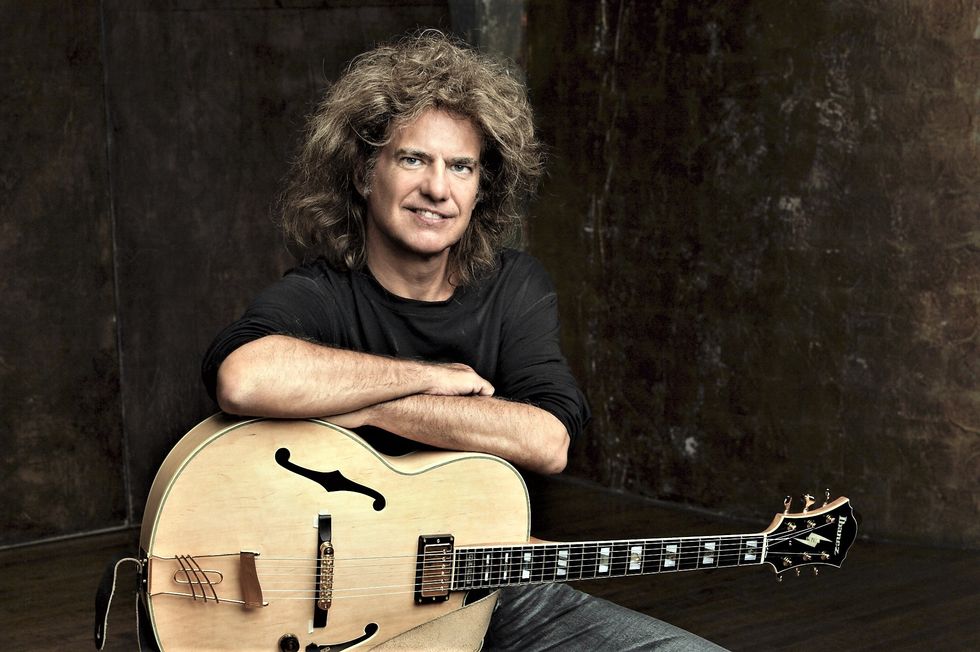

Bill King: Pat Metheny - A Document of Time

I interviewed Pat Metheny on two occasions, 1991/1998, for Jazz Report magazine. Metheny 36, was well beyond gracious in the length of time accorded me.

By Bill King

I interviewed Pat Metheny on two occasions, 1991/1998, for Jazz Report magazine. Metheny 36, was well beyond gracious in the length of time accorded me. In part one, Metheny is on tour in Rio de Janerio and made the call to my office – one expensive, unexpected call I'd never forget. Metheny was by then the number one touring jazz unit on the planet. Eight years later, with Metheny at age 43, I did a private sit down with the folks from Warner Music and press and interviewed. On each occasion, Metheny was in the moment, specific with answers, engaged and straightforward. Twenty Grammy Awards, fifty-plus recordings – each a revered document, numerous awards and citations for an artist whose childhood idols were Wes Montgomery, The Beatles and Miles Davis.

BK: I recently saw a repeat airing of your outdoor concert at the Montreal Jazz Festival from two summers ago. I think you drew almost 200,000 fans. This must have been tremendously gratifying.

Pat: Well, I don't know if it was that many, but it was a lot. Gratifying and terrifying. When I looked out there and saw that many people, I almost had a heart attack. I think the number I heard was 125,000 people.

The exciting thing for me was it was 125,000 people listening. It wasn't a street party vibe. The intensity of the listening, for a free outdoor concert, was pretty serious and quite an experience.

BK: I think the people were ready for that, this was a key event.

Pat: The Montreal Jazz Festival is a special thing for me anyway. I've played in one thing or another there almost every year since it started. I say this all the time…and believe…that of all the jazz festivals that I have been to all over the world, the Montreal one is still the best. The way that it's organized and the fact that they let each musician do their concert, as opposed to having a string of nine groups, on one stage. They seem to have respect for each band's unique thing. I think this approach is admirable.

BK: Your band plays impeccably. Rarely do bands sound this good live. How much preparation goes into readying the group for the road?

Pat: We spend a lot of time working on the details. The thing about the group is that it functions in a lot of ways like a modern big band. We write pretty seriously for the ensemble as well as setting up improvisational sections. Our ensemble happens to be synthesizers, sequencers and all that kind of stuff. For me, the only solution to that is to work on trying to get all details as right as they can be, so it does involve a lot of preparation.

BK: You've also been able to retain the same members for an extended period, and that's something very few bands can do nowadays. What's your formula?

Pat: Well, it's hard work, arduous work. Being such high-level musicians, everybody has a strong personality. It's imperative to me. I enjoy working with musicians over long periods because I feel that's when you get to the good stuff. I feel fortunate to have been able to do it; to sustain a group over a 10 or 15 year period and have each musician grow and be able to contribute different things at different times. I don't know what the secret is. It's an on-going process trying to keep everybody stimulated and happy.

BK: Are all the players satisfied with their roles?

Pat: Well, yeah, the thing is everybody, including myself, has something that they can do that they don't get to do in the context of the group. That's why all of us must do outside projects.

The group is a unique entity at this point. It's almost got a life of its own. We all get together to play and the first couple of rehearsals we are all kind of looking at each other like, "Wow, where does that sound come from?" It doesn't come from any one of us individually. It's a collective thing that has taken ten years or so to develop. It's a special thing. Of course, there are frustrations at different times, for different people, that's natural.

It's part of my job as a leader to try and accommodate everybody as much as possible, but at the same time, I have a really strong idea of how I want the group to sound. Part of my job is to set the limits. We're only going to go this far, we're going to do this, and we're not going to do that. Sometimes people are happier about that than others. I've always felt groups need influential leaders. Most of the groups that I've heard, which are co-op groups, just sort of let things go, and they are not as satisfying for me as a listener, as when I listen to groups with somebody making the decisions.

BK: When you decide it's time to record, do you have the total picture in mind, or do you just let things evolve?

Pat: Most of the compositional stuff comes from me. There are tunes that Lyle Mays, our piano player, and I work on together. Occasionally, Lyle brings in the material of his own.

I've always done most of the writing because part of the reason for me having a band is to have a vehicle for me as a composer. On the other hand, every lead sheet that I bring in, I write out a pretty elaborate set of parts for everybody, which immediately gets changed by them for the better. I count on that.

I'm never going to know as much about what makes a good bass part as Steve Rodby knows. He's dedicated his life to coming up with terrific bass parts, and he can do it at will. In that sense, everybody makes an incredible contribution. The difference in what I start with and what we end up with is often striking.

BK: You provide a framework and give your musicians the freedom to determine their parts.

Pat: This is also part of having worked with people for ten years or more. I know what they can do, so I write straightforward little things that I know they're going to turn into not so simple little things. That's part of the fun of playing with people for extended periods. I can say do this kind of thing, and they know what I'm talking about.

BK: One of your band's remarkable achievements is the balance attained between acoustic and synthetic technology. One is always sympathetic to the other. Do you strive for that equality?

Pat: It's been a fascinating issue for me. I've kind of grown up with that stuff, as has Lyle. The whole point of using synthesizers was never a controversial thing for either of us. Here they are, here we are. We're perfect for each other, so let's go.

I think it's different for the generation before us, like Chick, Herbie and those guys who were acoustic musicians for most of their careers and already established. Suddenly there were these new instruments thrust in front of them. For us, we kind of grew up with both.

My first act as a musician was to plug it in. That was before I even played a note. Electricity isn't an add-on for me; it's part of what I've always done. I've always concerned myself with trying to get a good sound. I try to use electricity creatively and responsibly, but my sound models have always been acoustically based.

For me, the ultimate sound is Wayne Shorter or Miles, or the sound Herbie gets on piano, or an orchestra, or acoustic bass. Those sounds to me are inherently more exciting than a sine wave.

I've always tried to get a certain level of harmonic complexity in the sounds. When I hear the way most other people use synthesizers, I don't know what they're thinking about. There is a lot more power in acoustic instruments. People often confuse the two because you can make electric instruments artificially louder, but acoustic instruments have many more balls. Acoustic instruments by their nature have a much more extensive dynamic range than any electronic mechanism; this is something we're always trying to compensate for.

When you think about the range of volume, you can get from a snare drum, from as soft as you can hit it, to as loud as you can hit it. No speaker in the world can recreate that dynamic range. So what you have to do with an electric instrument is trying to create an illusion of a broader dynamic range. That's something we spend a lot of time on with the group. We try to keep the power of the acoustic instruments there, but at the same time, we are all playing electric stuff.

BK: The sound of the '60s was the model thing: how would you describe the sound of today?

Pat: We are in an era of diversity now. In the '60s, there was always like a mean thing that was happening. When I look around, and I think well, there's my group doing what it's doing, and at the same time, there's Wynton doing something different. Charlie Haden with the Liberation Orchestra doing something different again. The thing now is diversity.

It was much simpler when it was chronologically oriented. You could see Coltrane's career: first bebop, then some extra notes, two drummers, then it was three, and later he died. It's not that simple now. There's this whole Pandora's Box of everything from rap to whatever available on to every musician on record of CD. They can go home, pop it on, and whatever they put on that night is what's happening right now. It's a different period. The world became a different place because of communications.

For me, I could play modal music all day long; it was part of the vocabulary I had to learn as a musician. A young kid right now is going to have to learn just like I did about every mode and everything about every chord scale and everything about why you need to go from this substitution to that substitution to get this effect.

The one thing about music that people often forget is that it's tough. There are no shortcuts to wisdom and understanding, and there never will be, regardless of how advanced computers get or how hip sequencers are. There is never going to be a substitute for understanding music. There will never be a shortcut either. I realized this at a young age, but I was also lucky to be around great musicians in Kansas City, where I grew up, who just didn't accept anything but the real stuff.

I have a pretty thorough understanding of harmony. I don't see how anybody could seriously become a contender for dealing with improvised music without understanding the whole vocabulary of what has happened in the last 100 years in American jazz. That will never change.

BK: Do you believe this is where a lot of musicians fall short?

Pat: I do. I see it most often in the fusion and the avant-garde categories where people don't have a thorough understanding of the basics of music. Even though stylistically, I'm not in the same camp as Wynton and the kind of younger cats coming up playing more '60s type of music, I'm thrilled to see that happen. I'll see Wynton, Marcus Roberts, and those guys way before I'd see almost any fusion group that I could name, just because I know I'm going to hear some music. People are dealing with the reality of music.

I'm sure that those guys are going to develop into something else. When I see people criticizing them, saying, "Well, they're just playing the '60s stuff rehashed," that's what I did. For the first ten years I played, I was looking at the music from 1960 to 1970 as a model. That is sort of what I built my thing on, which now, for whatever value it is, it's unique to me. I'm sure all those guys are going to do the same thing. They are building on something real as opposed to a chip in a computer.

BK: Are you satisfied, musically?

Pat: I'm never satisfied musically. I drive myself and everybody else crazy.

BK: Do you intentionally avoid repeating yourself compositionally and avoid familiarity?

Pat: I try. Everybody has their vocabulary of favourite things to go back to, but I'm always pushing myself to try not to do that. Sometimes, I give in because the urge to write something that is a specific sound is just so intense I have to do it. After the fact, I say, "Okay, that reminds me of this other thing I wrote once."

Eventually, you start to have a sound. I don't think you can reinvent yourself every time you write a tune. Some people have a particular set of things they like. Everybody from Duke Ellington tends to move within a specific range of sound. It's hard to know where to draw the line between doing that and repeating yourself.

BK: Do you store ideas on cassette and go back to them later?

Pat: I do, and I just lost my stash of cassettes. Eight years worth of little fragments; I'm bummed out about it. I have a lot of them backed up on the hard disk on the computer, so maybe I can recreate a lot of them. That's the way I usually do it. I keep a lot of notes and sketches of things and make little cassettes and demos. It's rare that we sit down and write together. In the early days of the group, we occasionally did. I will venture to say that was our worst stuff. Usually, I have a tune that's almost done, and Lyle helps me finish it. That's the way it works nine times out of ten. There were a couple of tunes which were his that I helped him finish.

Most of the writing has been songs that I have brought in for the group, and he's incredibly good at organizing and helping me finish things. I think he would be that way with almost anybody. He's a great collaborator. He has an idea about getting to what's good about a tune, eliminating the stuff that's unnecessary and coming up with something a little bit better.

BK: Does Lyle help create those lovely interludes?

Pat: Yes, he's good at transitions. He's also really good at endings—my two weakest spots.

BK: The synthetic colours and voice-instrument doubling Lyle and you created is now being copied by numerous crossover-fusion groups. Eventually, the idea may be as common as the DX7 Rhodes sound. Does this bother you?

Pat: We just have to do something else. It's a thing I've heard a couple of times now. I saw this phenomenon happening in a significant way with Jaco. It was no longer the Jaco Pastorius sound but became part of the jazz vocabulary. If you're a bass player, you have to be able to do this. To a lesser degree, this has happened to my guitar sound. You hear it on commercials and pop records. I know where that sound came from, but it doesn't matter anymore. That's where it came from because now it's just part of the overall thing. Nobody knows where this or that beat originated; they are all part of the picture now. All I can say is that it's kind of flattering that somebody somewhere like you thinks that I had something to do with it. At this point, it's better not to look back. For me, the only problem I have with it is I just wish a lot of it sounded better.

BK: Do you have a set-up you bring with you to compose on the road.

Pat: I don't compose on the road. Playing is such an all-encompassing thing, that the thought of playing a three-hour show and then going home and writing is sort of inconceivable. I work eight or nine one-nighters in a row with a day off, then eight or nine one-nighters and on and on. Our touring schedule is sort of famous for being among the most gruelling in all of the music business. We hit it hard when we hit it.

BK: Do you enjoy it?

Pat: I love it.

BK: How long had the concept for 'Question and Answer' been in the planning stages?

Pat: Three days. I was on the road with the group for basically 14 months playing group music. It was all of 1989, and I loved it. It was one of the best years we've ever had. For me, this always happens after about six or seven months of playing with the group. I start to get this itch to play with some of the older cats, like Jack (DeJohnette) or Charlie (Haden) or, in this case, Dave (Holland) and Roy (Haynes).

There is just something for me that happens when I play with those guys that is not the same in the group. It's a different kind of music. I've always been kind of lucky to play with master musicians a lot. I love it. There's nothing like being around cats who are older and more experienced than me. Even at the ripe old age of 36, I still feel like a young cat relative to most of the guys who are my heroes. The fact that I get the opportunity to play with these guys is something I wake up every morning and thank my lucky stars for.

In this case, I've played a lot with Roy over the years and played some with Dave. I always imagined those two guys would play great together, and I knew they never had; this was kind of fermenting in mind for most of last year. Ever since Jaco left town, I've had this feeling it is better not to wait to do things. He always talked about doing another record. We were best friends for 15 years, and when this cat left, I said, besides the fact that it's a drag, we're not going to get to make that record.

Whenever something is itching at me like this, I think, well, I should do it. At the end of the group tour, it was a couple of days before Christmas, and I knew I was going to have a few days in New York. My chops were in real good shape because I'd been playing a lot, so I made a call from the airport to the office and asked them to call Dave and Roy and see if they could make it. They were both available, so we did it in the Power Station. We recorded just for the fun of it.

BK: Were they pretty much first takes?

Pat: Everything is either first or second takes.

BK: Are you a big believer in first takes for this style of jazz?

Pat: For this kind of music, yes. Even though I've done fast records before, this one was the fastest. We went in at one in the afternoon and were done by seven. There are even five tunes that aren't on the record. I wrote four tunes the night before, the first things that came to my mind. I made little sketches of ideas. We did some standards, and a couple of songs I had lying around I hadn't recorded. We just had fun. We also didn't listen to any playbacks of anything. There was an engineer that I trusted. We just played.

I put the tape away and didn't even listen to it for a month. Gil Goldstein, who was at the session hanging out, also had a tape. He kept calling me every day saying man you should listen to this stuff. It's some of the best playing I have ever heard of you on record. I was kind of scared to listen to it. First of all, I thought I probably wouldn't like it. Then when I heard, I had to agree there was some of the most unselfconscious playing I've ever gotten on a recording.

I played it for the record company, and I liked it too. So, we put it out, and it's been a real successful record, which kind of surprised everybody. It's done almost as well as the group record.

BK: What do you listen to for your pleasure?

Pat: A lot of Coltrane, a lot of the Miles quintet stuff. I listen to a lot of Herbie. I've got a lot of tapes of just Herbie on other people's records. I still listen to a lot of Wes Montgomery. He's still the king, and there's no one even close.

I listen to a lot of contemporary records to hear what everyone else is doing. For me, the hands-down record of the year is John Scofield's Time On My Hands. Excellent, a triple plus record. Orchestral stuff, Steve Reich and John Adams. A lot of Debussy, Ravel and Eric Satie.

BK: Many thanks for sharing your time and insights with us.

Pat: My pleasure and good luck with the magazine, you guys are doing some hip stuff.

Metheny answered questions in complete paragraphs and with considerable thought. I always view him as a rarity – a great musician and communicator and musically passionate beyond comprehension. Now 1998.

BK: What distinguishes Imaginary Day from previous Pat Metheny Group recordings?

Pat: I think one of the things people have always appreciated and enjoyed about the group is the 'trip" factor. We do these pieces with extended looks at single musical ideas and try to develop them into eight to 12-minute pieces. We've had several tunes over the years like Are You Going With Me? and First Circle that have been long developed pieces.

We wanted to do that sort of thing throughout an album with a narrative shape for beginning to end. There have been a couple of other records – Secret Story and As Wichita Falls So Falls Wichita – where that has been the goal as well. It's kind of hard to believe that Lyle and I have been writing together for 20 years. And Steve and Paul have been our rhythm section for 15 years.

One of the challenges of this record was to take what was a somewhat different material, ranging from almost ethnic reference points and folk music to metal and techno, and see how we could reconcile those things. We didn't argue with the elements that showed up, but instead just worked with them.

One of the early pieces of this process was Imaginary Day. It started as a vehicle for this new instrument I was working on – the fretless guitar. We realized very quickly we'd written some kind of a Chinese/opera/fretless guitar blues tune.

There may have been a time when we would have agreed not to mess with that, but this time we decided to see if we could make it work within the band's voice. The thing I'm most proud of with this album is how we move through many different zones, yet the recording remains unmistakably true to our sound.

BK: Many of the new stringed instruments heard prominently on this album were crafted by Toronto based luthier Linda Manzer. Can you describe them and their function within the context of the unique original material?

Pat: Lots of times, a new sound will spark an original piece, and that's happened many times during working on instruments with Linda. Over the years, she has become one of the preeminent guitar-makers in the world. Canada should be very proud of her. For me, it's been very satisfying having the kind of relationship where I can imagine a sound and have her make an instrument that makes that sound come true.

In the case of this record, two pieces, in particular, fit the bill – the title track and Into The Dream, which is a feature for a 42 string Picasso guitar. It was the result of me scribbling an idea I had for a guitar on a piece of paper and Linda transforming it into a truly amazing musical instrument-a combination of guitar and harp Garrett's record, Pursuance, but this is the first track where featured.

BK: The first four tracks of Imaginary Day seem to be a reminder of the band's evolution over the past 15 years. Then a new writing technique emerges from the next track, A Story Within A Story, and carries on throughout the project. Is that an accurate observation?

Pat: Yes. One of the things that have happened with the last couple of records is that the writing collaboration between Lyle and I have gotten deeper and is much more fun.

We've always enjoyed writing together, but, at this point, given the body of work that exists under our collaborative names, we feel free just to let our imaginations go. The issue of style and idiom, which was never a big one for us, is now completely obliterated. We just try to give the listener an honest representation of what we hear while trying to create an environment that's inspiring to us as improvisers.

BK: Each of the expansive compositions on this record borrows from a variety of genres. An excellent example is The Roots Of Coincidence, which begins with an electro beat, pulsating synth line and hard rock drumming, and is then suddenly interrupted by various clipped samples and thundering guitar. It eventually dissolves into a brooding guitar solo layered over drummer Paul Wertico's crisp jazz cymbal work. Is this the Pat Metheny Group in transition?

Pat: That track is probably my favourite one on the record, and I like your description of it - it's very colourful. The piece goes on from there. At that point, we move into an almost contemporary classical chamber music piece. The exciting thing for me about that track is how it all fits together.

When I think about what I listen to as a fan of music, besides the obvious things like captivating melody, harmony and rhythm, which are fundamental things that make any piece of music work and sound good, there's one particular quality that jazz has been good at, the ability to document the feeling of a specific time in a way that only happens during the period when the music is recorded. I think that track has that quality. I can't imagine our band making a track like that happen even three years ago. The forces that were at work at that time made us play as we did then. Now that's over.

When I hear a Miles Davis record from the 1960s, I not only hear all this great music but can see how people walked and dressed and what the vibe was. When you hear a Louis Armstrong record from the 1930s or Ellington from the 1940s, you get all these pictures that are particular to that time. Somebody may be able to transcribe the notes, imitate the style or even try to make it an idiom, but for me, it's something much more precious than that. It's a document of the time.

BK: You've been able to experiment with a multitude of world rhythms, colours and influences and then escape the scorn of diehard jazz critics. Do you think the body of work you have originated beyond the group has pretty much silenced them?

Pat: Critically, I often hear people describe what I've done divided into two parts, the group and my other stuff that compensates for whatever. For me, the fact that Zero Tolerance For Silence and Secret Story were recorded within a few months of each other is important. That reflects something essential to who I am as a musician. But as I mentioned, most often, when people discuss my music, they usually break it down into their stylistic preferences.

My message, if there is one, is that there isn't a style. To me, the era of fashion being the primary identifying factor of an idiom has been irrelevant for a long, long time. It's much more about spirit, imagination and creativity. More and more, I realize I don't like or relate to the idea of jazz as an idiom. If anything, it's a process. To limit it reduces its potential. I've always seen best-improvised music as that which transcends style. Feelings and inspiration are the currency that it deals with.

BK: How difficult is it for Lyle Mays and you to begin the writing process after a long absence?

Pat: It's more fun than ever. There are a few essential things in the dynamic we have. One is a certain feeling of accomplishment with a body of work that reflects our 20 years together. There's not much that we've done together, which makes us cringe when we hear it now. Most of our recordings, even from the '80s, which could have been a potentially dangerous time for us, still sound pretty good. We never based our ideas on idiomatic things, but instead on how we heard something. We were never about reacting to things.

When we started working together, we were total reactionaries to what we thought was fusion. Our thing was trying to come up with a way of playing with a rhythm section that provided the time from the ride cymbal and upper part of the drum kit as opposed to a back-beat. At the time, I had no interest in playing anything with a fuzz-tone guitar or distorted kind of sounds. We eliminated that from our vocabulary as a possibility.

Other than that, we didn't have an agenda. Ironically, we now freely incorporate those elements that we rejected early on as a means of moving the music along. Now when Lyle and I write, we just really say, "What have you got?" We combine our best ideas and let them take us where they will. Often, the pieces emerge in ways that surprise both of us.

BK: Are there permutations made to the body of composition during rehearsals?

Pat: Definitely. We have changed our method of working, and I'm not so sure how much I like it. Before We Live Here, we always played the tunes live for at least a few months before recording. Secret Story was the first recording where the music was written for the record. I figured out how to play it live after the fact.

The rehearsal process is fundamental. It's the only time we get to see what we've got. Even decisions about how long a solo should run or how fast or slow a song should be, can't be entirely determined until you take it on the road. You just have to use your best judgment.

BK: Besides the considerable talents of your rhythm section, vocalists Mark Ledford and David Blamires bring an additional ten instruments to the mix. Has this given you greater latitude in reproducing live what's been captured in the studio?

Pat: Yes, in the case of this record, there is very little singing. The players are primarily used to colour the music in another way. The fact that they are such versatile musicians is fantastic for our live presentations. This time, we wanted to incorporate their other talents more in writing.

BK: Do you have plans to tour extensively in support of Imaginary Day?

Pat: We're going to hit it pretty hard. We're touring until next July. I don't know if we'll make it to South America this time. It's fun to go down there, but it's hard and expensive, and a little risky with the gear.

BK: Are you able to savour the unique cultural opportunities touring the world can offer?

Pat: We're pretty much in and out of places. When you do a world tour in six months as we do, you have an opportunity to experience something else very few people get to. Each night there are a few thousand people from all over the world sitting in front of you hearing your music. You begin to see the similarities between Brussels and Tokyo, between Minneapolis and Rio de Janeiro. You get this feeling of world culture in a way that very few people get to experience.

Even though you don't have time to go out and see the sites, you do get this incredible specimen of humanity sitting in front of you each night. You get to offer up a kind of litmus test to see how they react to this kind of music.

It's amazing how the vibe of the world is interconnected. Certain tunes, sounds, grooves, feelings and kinds of phrases resonate throughout the world, regardless of culture.