An Immigrant Song: I Can See Canada From The Rainbow Bridge, Pt. 3

I was relieved when the first break arrives. I slipped into the men’s room and was having a leak when this drunken character walks in and says, “Get the fuck away from the piss pot. I have a score to settle.” He then pulls out a handgun and shoots the urinal dead centre. My ears pop...

By Bill King

This is the 3rd installment of Bill King's epic story about turning to Canada and leaving a war-torn America. Part 1 can be viewed here, and Part 2 here.

The roar of Niagara Falls played tricks on the mind as we awaken from a restful sleep. It was as if we were suspended a foot above the rapids in our motel room. We shower away the previous day and prepare ourselves for the road up ahead.

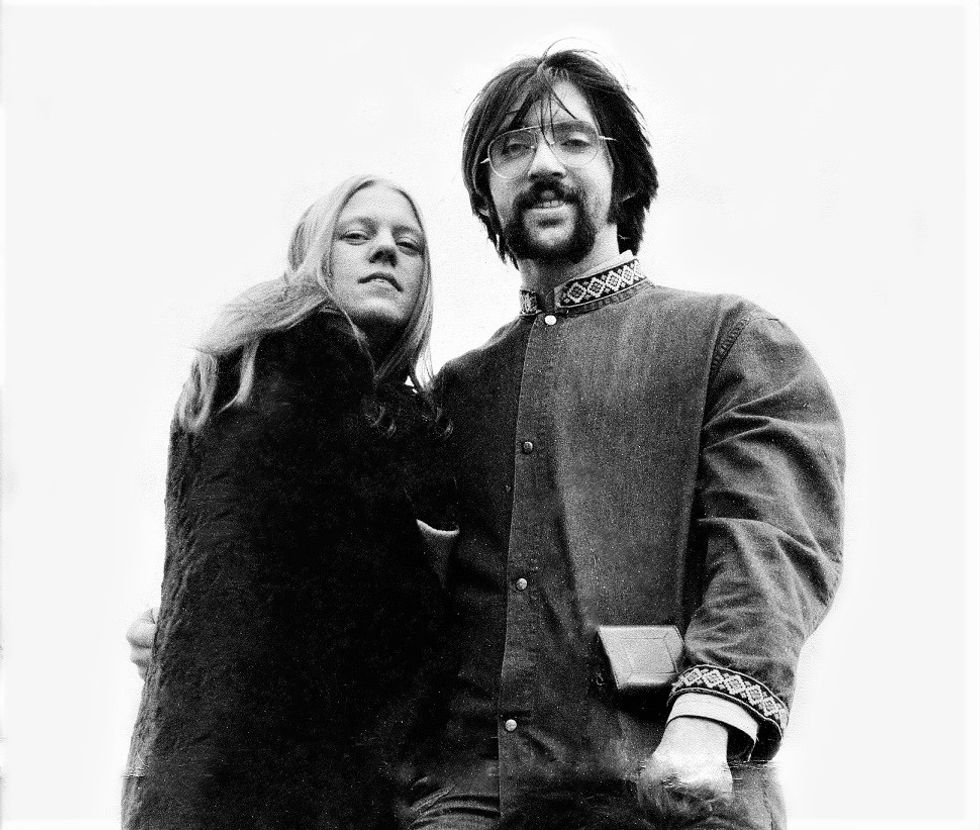

From the moment we met, I’d sold Kristine on Canada. She imagined a pastoral land much like the German countryside with long stretches of carefully manicured rolling hills; absent the intrusive Burma Shave signage we witnessed from roadside billboards and painted roof tops throughout the south.

I assured her there were no ghettos or districts given to poverty or derelicts and one could even ride between quaint European-style neighbourhoods on street cars much like San Francisco and people-watch from sidewalk cafés. It was an idyllic new world I planned for her.

Kristine and I hadn’t lost the will to hitchhike, even after an intense grilling at customs and immigration. It was imperative we get far out of sight of our interrogators and locate a highway leading to Toronto.

With thumbs extended, we hitch a ride with a well-dressed businessman who offers to drop us close to the city. Nothing exceptional about the drive other than that the both of us grin a lot and poke each other in the ribs. Near the Jameson Avenue exit, the gentleman pulls over and wishes us well.

The early morning hours are backlit by a welcoming October sun. The two of us poorly dressed for the eventful day. Kristine wore a light sweater, jeans and sandals. Me? Desert boots, jeans and light denim jacket. Wrong clothing to combat a brisk autumn wind that wasn’t playing favours.

I often think of this moment and how other immigrants must feel when they first arrive in a new land. That walk along Jameson Avenue is forever etched in my memory.

There were feelings of helplessness. Moments of laughter, fear, anxiety and curiosity. The surrounding apartments looked like familiar 1960s austerity housing. We couldn’t help but wonder what it would be like to reside in one of those places. No money worries about rent, food or employment. Or how grand it must be to sleep in a heated room in one’s own bed. To read a book or watch an old movie and know the following morning you weren’t facing eviction or pressured with impossible demands.

Before leaving the States, I called Albert Grossman's office. Even though I mysteriously disappeared after Janis’s gig in Memphis, there were no hard feelings. In fact, I was told I should have asked for help. The agency had been successful in dealing with artists who had draft problems.

I asked for agent Vinnie Fusco, who had kindly steered me through the mechanics of copping the gig with Janis and who was a big supporter of mine. Vinnie wasn’t available. I was then patched through to his partner, Elliot Mazer. I explained what had happened following Memphis and the fact I’d just served ten months in the military and was heading to Canada. Instead of hanging up on me, Elliot suggested I hook up with folk singer Adam Mitchell. He felt Adam would be sympathetic to our situation. Elliot gave me a phone number and street address.

I clutched a small suitcase with nearly all our possessions in my left hand. The other? A reel to reel, Sony tape recorder.

The walk from Jameson Avenue to 10 Hazelton Avenue in Yorkville area was an exhausting seventeen kilometres. Along the way, Kristine and I examine nearly every structure. We witness a radical change from the colourless 1960s style housing of Jameson to the large, ornate brick-laden houses only steps away from Parkdale Village. This was the city I’d promised Kristine.

One can assume the arrival of the unannounced and unknown would be shocking, yet Adam and his young wife Carolyn invite us in. We arrive just as dinner is being set and company already situated around an oak dining room table.

After a bit of small talk, Adam invites us to sleep on the living room couch and floor until the following morning and then welcomes us to stay for dinner. The menu? Chicken L'orange. Entertainment? A night of Euchre – the card game.

There’s no way an encounter as such doesn’t come with a certain amount of apprehension. We understood we were outsiders. Carolyn went out of her way to offer her guests a night of normalcy; free from worry and uncertainty.

Early October 17, Kristine and I begin canvassing nearby neighbourhoods in search of temporary shelter. After a few failed attempts, we locate a vacant front room at 43 Chicora Avenue, just off Avenue Road, south of Dupont. It’s three days out from Kristine’s 20th birthday, and we’re still getting our bearings. We pay the week’s rent.

October 20th, we celebrate Kristine’s birthday mostly secure in a warm bed. Then divide the celebratory lemon merengue birthday pie and revel in the joy of the moment. The following morning, I begin looking for work.

With money quickly running out, I assume the most logical course of employment was a visit to the musician’s union. In my home area, Louisville, Kentucky, and in Las Vegas, and Los Angeles, I was able to quickly secure work by hanging around the musicians’ exchange floor. I’d inspect a few bulletin boards at the various union halls and make a few inquiries. The vibe was one of brotherhood and friendship. I contemplated what the reception here would be like for a guy with no papers or permanent address.

I slip through the doorway of the Toronto Musicians Association and spot a bulletin board pinned with an assortment of note cards. As I’m sorting through the various band adverts, I’m approached by a young man of Jamaican descent and his red-haired girlfriend. He asks what instrument I play. I respond, ‘keyboards.’ He then introduces himself as Trevor and mentions a booking in Quebec he’d accepted for November 18th week and asked if I was interested. It paid $200. Those words sounded as if spoken by God.

Trevor booked a rehearsal space in the union hall outfitted with a piano. Off to the side, a drum kit sat along with a small bass amp. It just so happens Trevor’s girlfriend, Elizabeth, was playing bass. The three of us run though a short list of middle-of-the-road songs with the winning ticket – a couple of radio-friendly hits: “The Green, Green Grass of Home” by Tom Jones and “Little Green Apples” by O.C. Smith, amongst a few well-loved Johnny Cash classics.

I’m now more than curious about this young black man and his connection to country music. Only Charlie Pride came to mind as a person of color in the genre. Trevor explained that country music always played in his parent’s home and it spoke to him on terms he understood. Even with a short playlist and four-set night ahead, I kept in mind I’d still be $200 richer.

Those final days stationed at Ft. Campbell, Kentucky were twice interrupted when I fell violently ill. On both occasions, I’d slither into the post hospital, roar in pain for hours, then be sent home carrying a handful of (placebo) tablets meant for a stomach condition called gastritis. The second and most severe episode erupted while I was playing a ‘change of command’ ceremonial dinner amongst a roomful of decorated officers in dress blues; accompanied by their stylish wives.

I’m in full military apparel, every button and medal sporting a lustrous shine. Even my shoes reflected the outline of my pant cuffs. As I step towards the stage, I unexpectedly collapse in pain, roll over and lock in fetal position. Those closest to the bandstand look on in horror. Standing nearby, a sideman clutching a trumpet lifts me up and walks me from the room and to the post hospital. I spend the next hour or so tramping back and forth to the bathroom and severely vomiting. Once again, the diagnosis - gastritis. Kristine is having none of this. She fights back asking for a proper doctor and examination. No go.

It’s late evening October 23rd, and I’m starting to feel sick again. Throughout the day I’d throw-up. And then the sickness would pass. Early the 24th, the seizures begin to arrive one after the other until I could barely stand. It was that surreal journey from our room to the bathroom that convinced me I was in serious trouble.

Kristine bolts from the rooming house and makes her way to a corner variety store at MacPherson and Avenue Road. She enters crying. The shop-owner asks her what’s going on. The kindly woman hands her two transit tokens and insists Kristine take me immediately to Mt. Sinai Hospital. She emphasizes it’s the best hospital in Toronto and they will take good care of her husband.

By bus, we work our way down Avenue Road to the emergency room. Kristine explains to the attendants our situation and my symptoms. I’m wheeled into a back room and examined. The lead examiner presses down my rib cage into the depths of my stomach. That’s when I howl in pain. “It’s his appendix; it has got to come out,” he says to a group of on-duty physicians.

I remember the conversation as if I’m still lying before the same crew. “Does he have insurance? No! It says on his admission papers, he’s new to Canada and has no coverage.” There’s like four people hovering above when another asks, “So, what are we going to do?” A pause. “What do you mean, what are we going to do? We’re going to operate. We’re not leaving him here like this,” says a young doctor.

Fully aware of what’s going on, I’m wheeled into surgery and given a local anaesthetic. Within minutes, I can feel a surgeon trace the infected area and begin cutting. Blood spurts from the fresh cut and rolls about my waist as a hand reaches out to wipe me clean. I’m still conscious and witnessing this.

“Take the clamp and hold it still,” orders the surgeon. Then panic sets in. “What are you doing, what are you doing,’ he shouts. “Can’t you see fluid is leaking from his appendix?,” he asks. The body convulses. The head, the legs, and arms begin to violently tremble. Then a cold rush covers over me, and I begin to drift from consciousness into a dream state and can barely hear my caretakers' vocal exchanges. Then lights out. The infection quickly spreads inside my abdominal cavity into the bloodstream. I’d just experienced toxic shock.

Hours later, I come to and can feel the pain from the incision and hear Kristine’s voice console me. When I return to consciousness, I see her angelic presence, tears in her eyes, and the uniform of a nurse going about her daily routine. I’m alive! Kristine keeps repeating, “you nearly died, you nearly died.” I’m so medicated the words make little sense. The next six days are spent recuperating. Kristine rarely leaves my side.

We needed help. A quick fix. There were few dollars left. It was pointless asking family. Pops cut me out of his life. It would be three years before we’d have a true conversation. The folks came up in 1971 for a visit and left the same day. Pops became furious when Kris and I gave him the People’s Almanac as a gift. He proclaimed it communist literature.

Mom pleads for me to return and face the consequences. There was never anything about these calls that offered hope, compassion or aid. My saving grace was my younger sister Karen. She loved her big brother without prejudice. My younger brother was far away, stationed in South Korea. Karen kept me in the loop and informed of family issues during the six years living in exile.

Do you want to experience what it’s like to be alone in the world? Illness, misfortune and petty differences can leave a loved one prisoner of their tribulations. People marry for a variety of reasons. It’s those hours when you face ‘end of life’ consequences and nearby, that person you bonded under the purest of intentions, holds your hand, whispers in your ear, and reminds you, that you’re the most loved and important person on the planet to them. It’s all about renewal and hope.

During my hospital stay, Kristine begins seeking out organisations that support war resisters. It was the kind people at Mt. Saini Hospital who recommend AMEX – American Military Exiles in Canada. After a visit with Jack Calhoun; the primary voice and activist/journalist for the newspaper/organisation, a family in Thornhill, Ontario was contacted and agreed to take us in and allowed me time to recuperate in exchange for Kristine working as a domestic.

The McMonagles – Robert and Christine of Thornhill – let us stay for a three-week period. Robert was a sales manager/executive at a major trailer manufacturer and Christine was a social activist committed to a variety causes. Christine seemed to be eager to discuss U.S. politics. In fact, during our stay we gather around a table of invited guests and are peppered with questions. There were a few local politicians and their wives in the mix. I wasn’t sure if we were being played or was this a sincere attempt to understand us. I was pressured more than once to denounce my country of origin; but I wasn’t going there. That wasn’t the issue for Kristine and me. It was the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

To this day, there is this misconception when the crazies grab the reigns in America, that the country as a whole shares the same beliefs. Not the case! For example, you can hang around any military base in America and get a variety of political opinions much different than the glossy image of soldiers all parading in lockstep. It’s still just people.

Kristine feeds and ushers the children off to school. She also washes floors, dishes, scrubs bathrooms, makes the beds and attends to me. It wasn’t long before I slowly regain strength and drag myself over to a piano stool. The McMonagles had an old upright piano sorely in need of tuning. None of that mattered to me. I just wanted to reacquaint myself with the instrument and renew my love-affair with those eighty-eight keys.

It was here I begin to compose. Kristine and I had no supplies; no pens or paper. We’d scrounge around for any useable tools.

The songs began to write themselves. I honestly can’t say if any were of merit. Although a lyric-book of the time is still somewhere buried on a shelf, I’m not one to revisit.

By November 18, I’m confident I’d be well enough to make the gig in Quebec. What I didn’t know was ‘place and distance’. Trevor assured me it was only a few hours away. Oh man, this was insane. “Three Rivers Quebec” (Trois-Rivières) is six hundred and eighty kilometres from Toronto. A 7-10-hour drive.

As we begin the long haul, there were few words shared between three people with little in common. Trevor was soft-spoken and Elizabeth, in a complete fog. Situated in the back seat, I shift from one position to another hoping the stitches wouldn’t snap and bleeding start.

Somewhere a good distance from the city we make an unexpected detour through back country amongst tall pines; hemmed in by snowbanks. Near the night horizon, I spot the neon glow of what looks to be a misplaced country and western bar. No shit – we were dead centre in a logging community. Only yards from an icy river.

Inside, I witness table after table jammed with men attired in plaid flannel shirts, ball caps at attention, and beers hoisted high above their heads. It was as if surviving the inhospitable surroundings was something to cheer about.

Trevor nears the bar and asks for the manager or owner. The bartender recoils, “why are you here?” Trevor goes on to inform him we are the band, hired for the week. He looks us over and nearly shits, then asks, “Who’s she?” “She’s my girlfriend and the bass player.” The man pauses then says, “But she’s white and you are as black as night.” He then turns to me. “What do you have too do with this?” I explain I’m the piano player. “The piano is over there, start playing.” What?

Trevor reiterates the fact we’d been hired for the week and would only play our contracted sets. The guy then signals a flunky over. “Go get these folks their rooms and keep those two separate.”

The door opens, and there it is. The room of all my nightmares. A wire cot situated near a long window in the corner. A broken desk. No towels or washcloths. No television or telephone. I debate out loud, how I could make this work. From beyond my window, I see the silhouette of an animal outlined by a moon-lit sky and hear the mournful howl of a lone wolf near the banks of the near-frozen river.

At the far end of the hallway, I locate a telephone then phone Kristine and tell her I’d more than likely feed myself to the wolves than spend another night here.

A floor below, the cowboys are baying at the moon or possibly chanting for another beer. Trevor, Elizabeth and I set up and begin playing. Two songs in, a lone stranger stumbles over and informs us we aren’t a country band and asks, who the fuck hired us.

The first set is a near disaster. Every second tune a logger would pass by, “Play 'Green, Green Grass of Home.'” I’d respond. “But we just played it.” Again, the response, “I don’t give a fuck, play it. I don’t want to hear that other shit.” Then Trevor says, "I do Johnny Cash too.” The guy looks directly at Trevor and says. “Have you seen yourself in the mirror. You ain’t Johnny Cash. Who is she supposed to be, Willie Nelson?”

I was relieved when the first break arrives. I slipped into the men’s room and was having a leak when this drunken character walks in and says, “Get the fuck away from the piss pot. I have a score to settle.” He then pulls out a handgun and shoots the urinal dead centre. My ears pop. Seriously, the gunslinger blows the urinal enamel shell in half. He then looks at me and says. “feels much better doesn’t it.” The reward for urinal murder? A beer and banishment from the club.

We endure the night; the catcalls and insults. Next morning, we get a visit from one of the house crew. “The owner’s back and he’s pissed, and you better pack your things and get downstairs,” he says.

We make our way to a row of café size tables and are greeted with, “I hear you people stink, and I want you to pack up and get the fuck out of here.” Trevor tries diplomacy. No go.

“Listen, young man. You come in here with a white girl and stay upstairs in my hotel and fuck her and you have advice for me. Here’s what I have to say to you. Get the hell out of here before I shoot everyone.”

I reside outside this conversation, then interject. This would make a great Dave Chapelle skit. “But sir, we have a union contract that says you owe us $600 for this week. In fact, since you didn’t give us notice we will have to sue you for two weeks pay.”

“Who the hell are you? The band’s attorney?”

“No sir, the piano player.”

“OK piano player, here’s the deal. Since you are such a fine negotiator and I feel bad the three of you come all of this way. I’m giving you $60 to go home, and we settle right here. You pack your things, and I don’t shoot your asses. Deal?” “But sir, we have a contract,” I respond. That’s when Trevor agrees to the deal and scoops up the sixty dollars.

Snow fell at such an alarming tempo, we could barely see the road ahead. This would be the all-time long-haul nightmare. I’m weaving back in forth in the rear seat, writhing in pain with eyes pasted on the road ahead. It’s like I’d fallen into an hallucinatory state. Every twenty miles or so the lone face of a wild deer would appear only feet from the car windows. It was framed like a ghostly portrait. Then fades back into the ominous white spaces. I’m guessing it took us a good seventeen hours of non-stop driving before we hit Toronto city limits.

I stumble in and hand Kristine the twenty dollars. She looks back at me and laughs and then reminds me. The only thing she cares about is having her baby safely home and insists I never take another gig like this ever. I wish life were just that uncomplicated. But there would be many others.

The next day Kristine and I make our way to Toronto to catch the film Easy Rider. It was one of those ‘must do’ moments. The film put us in an upbeat mood and feeling a bit liberated until the following morning when we come across a note addressed to us left on the kitchen table, asking us to go. The reason, I had mixed butter and jelly together and soiled the raspberry preserves. I wish I could have apologized for the gross violation, but there was no one in sight. Kristine and I pack our possessions and head towards Toronto.

Fortunately, we were able to secure a room in a men’s residence at 51 Madison Avenue. Two days pass when the house manager informs us we have to leave. There were complaints from other roomers that a woman was holed up in this private enclave for men. This was seriously laughable in that we stayed to ourselves and the room was to our liking. Unbeknownst to us, we’d accidentally rented in a ‘no- straights’ residence.

I posted a notice on a bulletin board at Long & McQuade’s on Yonge Street. I include the usual background information. Worked with Janis Joplin, Chuck Berry, Linda Ronstadt, and studied with Oscar Peterson and Jamey Aebersold. I hear nothing until I’m contacted by a bar band called “The Marcatos," led by brothers Fran and John Webster.

I drop by their eight-room apartment at 136A Hallam Street in Toronto’s west end, above a grocery store. The spacious digs came with a large living room outfitted with drums, piano and guitar amps. The audition went better than planned. Kristine and I land a room within the premises.

The Marcatos played an assortment of Creedence Clearwater, The Band, Joe Cocker and enough hits to work a steady week-long gig. Beside Fran and John Webster; pianist Scott Cushnie (Ronnie Hawkins) was holed up down the hall, as well as bassist Rick Birkett and a singer named Tony.

This was the ideal situation to focus on music and secure a minimum amount of security. Guitarist Freddy Keeler would also drop by. Drummer Frank DeFelice rehearsed with Bob Yoeman and Cushnie for their righteous project, Jericho – the music of The Band. “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, still reverberates through my brain.

The weeks ahead the Marcatos play a variety of clubs including the Richmond Inn in Richmond Hill. What always stays with me from this gig is meeting the Good Brothers and Gordon Lightfoot and hanging out with them in a friend’s kitchen singing everything from The Rolling Stones to country classics.

The Kings arrive!

It was a network of musicians who become our life support. It was also that community of American military exiles who would gather three days a week and play basketball. This also included Rick James. There wasn’t a whole lot of talk about war or returning home, it was more about our future in Canada. Some had landed teaching gigs, while others moved into media and other fields of expertise. Most never paused long enough to bandage old wounds. We healed by doing. One ball player was wanted for fire-bombing his alma mater. He stayed on the run. Another from Ohio who I had spent more than a few evenings with smoking camel shit sold as Lebanese hash, committed suicide when he returned to the states.

Kristine and I are forever thankful for the decades that followed. Our Canadian family has grown and continues to expand. Even today, we still pause walking up Jameson Avenue and identify a building we thought could have been the first stop and consider what it’s like to live freely in a country in which we’ve now spent more than two-thirds of our life. When we hear the dissonant calls to deport and punish those who come from afar, we know exactly how those words hurt and inflame. We are all immigrants.

Three years pass and Christine McMonagle locates me. Husband Robert and she have been following the publicity and airplay behind my Capitol Records debut, Goodbye Superdad. She’s part of a charity event being staged at Maple Leaf Gardens for McDonalds and invites me to sit in the celebrity section. This was something new for me, in as much as I don’t in anyway feel like a celebrity or suspect I'm on most people’s radar. I’m seated between Canadian boxing champ Clyde Gray and hockey great King Clancy. As we stand for the national anthem, I hear the opening strains of “Oh Canada” and see the eyes of these revered men look upward at the Canadian flag and banners of past greats hanging in all their glory, and feel a rush of patriotism, and think to myself, I’m here to stay. Home, at last!